Czechoslovakia  Nevada

Nevada

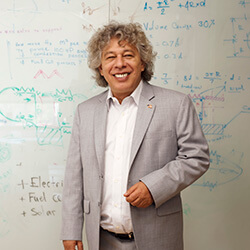

Daniel Pohl

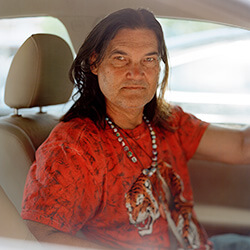

The Communists never liked my family. At home, my parents steered clear of political issues because my father had been in prison for punching a Communist informant. I never understood what was happening to our country and why we couldn't leave. Why did I need to call everyone comrade? Then I met a man named Marcus in karate class — he was a kind of "mad scientist" who made his living as a lumberjack. He was older than me, 35, and explained to me what was happening to our country.

I was a 19-year-old railway tech graduate running yoga sessions, religious discussions, and a raw-food movement in my hometown of Litomysl, Czechoslovakia. To the Communists, I was a dangerous spiritual gangster. Together, Marcus and I decided to escape the iron curtain.

First we decided to flee on foot, but we were caught on the Slovak/Hungarian border and grilled by the secret police for 48 hours. Then we tried to build a hot air balloon, but we found out someone else had already done it and the government was watching the skies. We attached motors to illegal hang gliders, but neither one of us wanted to be shot down from high in the air onto coils of razor-bladed barbed wire. We thought of building a submarine or at least semi-submersible. Everything failed. Finally, we came up with an insane idea. It was so crazy that no one had ever done it before. We were going to zip-line out of the country on a power line. It took seven to eight months to plan and execute this escape.

We worked on our equipment in Marcus's cellar mainly during the nights for five weeks. We would have had the contraptions done a lot faster if it weren't for one Mr. Nedoma, a nosy man who lived in the apartment complex and who was constantly snooping around. Being a commie "favorite sweetheart" as he was, he had a suspicion that something anti-government was cooking down in the cellar. We used collapsible seats and attached them to pipes found at the dump. On my night shifts at the train station, I occasionally unscrewed aluminum handlebars from the passenger trains and snuck them home in my ski sack. We constructed these brilliant and unique contraptions, which were designed proportionally to be carried in our backpacks. We now had the chariots, which we'd ride to our freedom.

We looked at many power lines, but there was no Google and it was difficult to know where they would take us. Finally, by hanging with local drunkards who knew the area, we found a dead power line at a nuclear plant that crossed the border into Austria. We got our equipment ready: Each pulley had a little wheel that fit over the wire. A sturdy rod was attached to the wheel and fitted with a small seat. We would sit on the seat with the rod between our legs and hold on — when we first took off we would essentially be going downhill, but when we got to the middle of the wire we would have to pull ourselves the rest of the way with our own strength. With fifty pounds of supplies on each of our backs, we would have to reach out and still keep our balance while hanging over 175 feet of empty space.

It was night, so we couldn't see anything. Marcus went first. It was amazing how quickly he disappeared into the blackness. The speed we picked up was mind-boggling. Then we had to pull. Inch by inch we advanced across the sagging line. In the middle of the journey we were so heavy we sank dangerously close to the live high-voltage wires that ran beneath us. I thought we wouldn't make it. As we went right above the border guards' heads, I had a horrible image of our bodies with current passing directly through them, superheating the moisture and expanding the fluid in our cells until we exploded. But after a long hour, we made it.

When I got to America, I worked as a food server in a restaurant and as a landscaper. But I was in Boston, and the Northeast weather was taking a severe toll on my health and often made me wonder: How exactly did the Pilgrims make it? I seriously entertained the thought of migrating to a warmer climate — and a Catholic priest played a decisive role in my decision. I shared with the priest that the church I was attending was more like a Christian version of the Taliban, and that I needed a break, a normal new life. The priest took me to a strip club called Golden Banana, and after we had an absolutely epic experience, he told me: "Son, you really think this place is great? This place is a dive, believe me. You should go to Vegas to see the real deal." It didn't take long, and I went to Vegas.