India  Utah

Utah

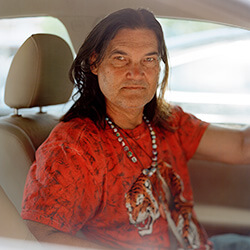

Kunal Sah

I was five years old when we moved into the motel in Green River, Utah. My family had immigrated to California from India in 1990, and for seven years my father worked odd jobs: dishwasher at Pizza Hut, burrito roller at Taco Bell, line cook at Jack in the Box. He saved every cent to buy that little independent motel.

I'd follow my parents around while they cleaned rooms. I put on pillowcases and folded towels and made sure there was fresh toilet paper in the bathroom. When it was lunchtime, my dad would run to Arby's in the little Nissan Sentra he had and get ten bucks' worth of food. It'd be chicken tenders and some potato cakes and curly fries and mozzarella sticks, and we'd eat. Then we'd get to working again.

We worked on that The Budget Inn for about four years. My parents wouldn't hire any staff. They were just saving money. They saved and saved and finally had enough for a Ramada Limited. My father bought some land, had a hotel built from the ground up, and in 2002 was issued the Ramada franchise banner.

All my other friends in town, they were always just getting yelled at by their moms and dads. But my mom and dad, they knew how to do it right. When I finally got the hang of riding a bike, my parents had a manager cover for both of them so we could all ride together. Sometimes my dad would get this look of conviction in his eyes, and he'd look at me straight and say, "You are the best in whatever you do. You can be the best. This is all up to you now. This is all up to you."

I still remember the day, July 7, 2006, when they packed their bags. My mother and father had been fighting a deportation order they received in 2004, and their citizenship had been pending for 14 years. I was 11 years old. They were not being deported on the basis of criminal activity. They were being deported just because their citizenship application was in queue since 1990 and their time was up.

My dad asked his brother to move to Green River to be my guardian and take care of the Ramada. But he became abusive. If I missed the bus or came home five minutes late from school, I would get beaten. One time I put my name in to run for class president. I told my uncle, and he beat me with a broom. I was a 4.0 student; I wanted to go to an Ivy League college and then become a neurosurgeon. That was my goal. "You can't do that." That's what he'd tell me. "You cannot be a doctor. You can't." That was the only grown-up voice I had in my household, telling me that.

I had made a minor career out of competing in the Scripps National Spelling Bee. My eighth grade year was my last chance. I was desperate to win. I wanted to bring attention to what happened to my parents. For ten hours a day I'd sit with my Webster's Third New International Dictionary. It's 2,600 pages, and I would go page by page writing words down that were new or challenging to me. I'd study roots and language of origins, prefixes and suffixes.

I made it into the finals that year. We went to the White House so they could film a segment to introduce the spellers, before the prime-time broadcasts. We met Laura Bush. Everyone was given a chance to introduce themselves to the First Lady. When my turn came, I said, "I am Kunal Sah, and I want my parents back. I really need some help. Please." I was sitting on the floor in a circle with all these spellers, and I start crying. "All these kids here that are with me, their moms and dads are here. Mine should be, too." That's all I told her. Mrs. Bush walked over and consoled me a little bit; she said, "This is something that we can address if you write to my office." It was a generic answer. "Write to our office"? "We'll address it"? Come on. I had been doing that for the past two years. My dad had. My mom had. I had written to congressmen — Jim Matheson and Orrin Hatch, and all of the representatives of Utah. A few years later, I'd write to Obama's office nearly every day.

I was the first one eliminated in the final. I ended up taking thirteenth.

I returned to Utah depressed, afraid, angry. This is my parents' house, I thought. My dad built this from the ground up. This is their place. I turned 12 and then 13, 14, and 15 years old, each day playing the role of my mother and father. Trying to maintain my GPA, but more importantly keeping their business afloat. My uncle would be drinking beer on the lobby couch, and I'd be doing hotel laundry, washing and drying the linens, renting rooms. Setting up breakfast in the morning before I took off for school. It was just overwhelming. It was too much.

My uncle went to India for a few weeks, leaving me to run the hotel full-time. I hadn't seen much of anyone in days, so when friends asked if they could come hang by the hotel pool, I told them sure. They arrived with a rack of Budweiser. I figured it'd be okay; it was a slow night. I cracked a beer. Within an hour, the cops arrived. We weren't being rowdy or loud. Some kid who hadn't been invited tipped them off. But because the drinking took place at my house, I was the one charged with serving alcohol to minors. It didn't matter that I had good grades and no previous charges; that my teachers thought highly of me and that I wanted to be a doctor one day. I was sentenced to 46 days in detention. Suddenly I'm in a jail cell at 15 years old. It was my sophomore year and I was kicked out of school.

When I was released, I was placed in foster care for two years, in a town about an hour outside Green River. I finished my senior year of high school online. I never got a graduation ceremony. I never got a prom. I didn't go to college. When I turned 18, my uncle called. "I don't want to do this anymore. I can't do this. I'm leaving. I'm leaving your property and you can do what you want with it."

I returned to Green River to take over operations. In my more than two-year absence, the hotel had been neglected. Every aspect of the place. The walls were damaged. The carpets were stained. Stucco was chipping off the outside of the building. The roof was missing shingles. The pool and hot tub were disgusting.

I found myself in a daze. I'm talking to the banks, I'm talking to my accountant about things and I don't even know what they mean. I don't know what quarterly tax is. I don't know any of this shit and it's all just blowing over my head. I'm lost, not knowing what to do or who to call. The hotel is everything. It was, it is, our home. We lived in an apartment right behind the front desk. And I just don't know what to do.

So I start with what my parents and I did together when I was a kid. I put on clean pillowcases and sheets, fold fresh towels, and replace the toilet paper. And then I pull hair from the drains, scrub at the walls and carpets, rake the leaves, and sweep the dirt around the pool. But most importantly, I'm at the front desk. I'm on the phone. I'm there. People see my face and they hear my voice and they have the assurance that their lodging will be okay.

In 2015, my dad calls and says, "I got a letter from the United States Citizenship and Immigration Services. It has interview dates for me and your mother. December eighth." I couldn't speak. I just hung up the phone and sat there. I looked around and thought, Everything's about to change.

My parents returned to the States in January 2016. We'd been apart for ten and a half years. Spotting them at the airport terminal, weaving through the crowd toward them, it was surreal. My dad's hair is gray. It was black when I last saw him. To see the look on my mother's face, to see the joy, but also the pain that's been in her eyes for the past 10 years, being away from her only child. I don't know. You only see that type of stuff in movies.

Since they've returned, we've raised the hotel on TripAdvisor from tenth best in Green River to second best. With their help, the skills I developed while they were gone can suddenly be used not just to stay afloat, but for progress. Actual progress. But I'm my own man now. And even though we're back together, our conversations are still mostly all about work. Nothing else. That hurts. I'm sure they want to reach out just as much as I want to, but we don't know how to talk about things after so much time apart.