Since graduating first in his class from New York's Webb Institute, a preeminent undergraduate naval architecture school, Johnson has traveled the world with his laptop, building 3-D models and helping refloat sunken things. He was on the team that recovered the Japanese fishing trawler sunk by a US submarine off Hawaii in 2001, and he oversaw a system to lift a submerged F-14 from 220 feet of water near San Diego in 2004. In his free time, he wins boat races in which the skippers build their vessels from scratch in six hours or less.

But so far, Johnson has refloated only vessels that are already sunk. Most days, he's cooped up in an office at the port, waiting for something exciting to happen. His skills don't go to waste — he's particularly well known for designing a 76-foot tugboat able to navigate rivers as shallow as 3 feet. But Johnson wants more; he wants to be one of those guys who drops onto the deck of a sinking ship and saves the day.

He's about to get his chance. His office calls: Rich Habib wants him on a salvage job for the history books — one Johnson might have missed if not for a lucky break. Habib's usual 3-D modeler, Phil Reed, is visiting his in-laws in Chicago, and his wife won't let him go to Alaska. He recommends Johnson, who has worked with Habib once before.

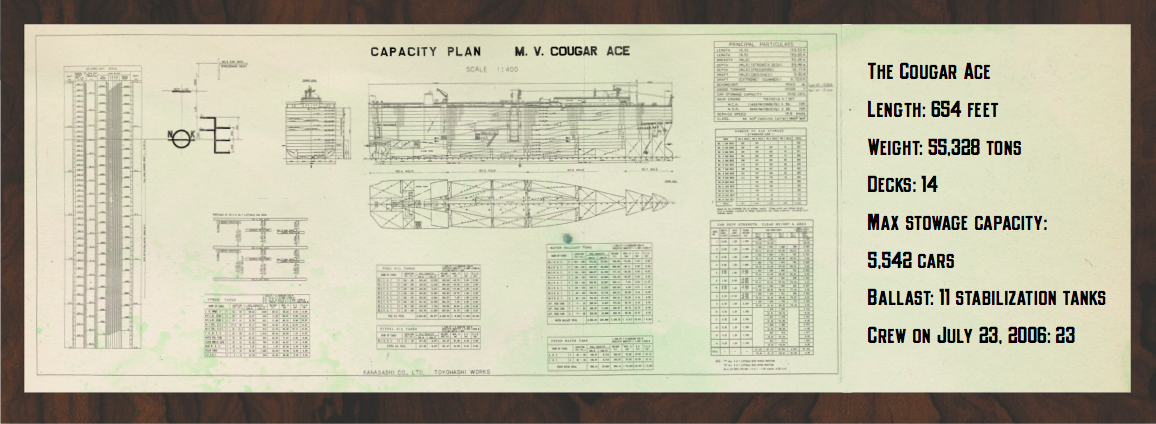

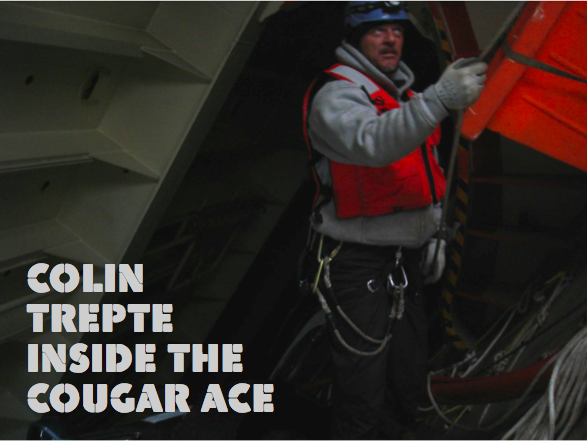

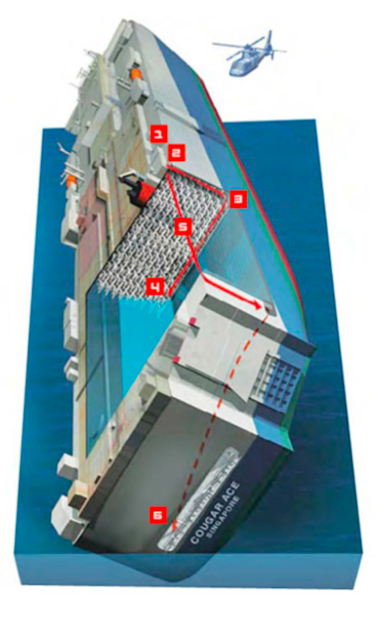

The job is daunting: Board the Cougar Ace with the team and build an on-the-fly digital replica of the ship. The car carrier has 33 tanks containing fuel, freshwater, and ballast. The amount of fluid in each tank affects the way the ship moves at sea, as does the weight and placement of the cargo. It's a complex system when the ship is upright and undamaged. When the cargo holds take on seawater or the ship rolls off-center — both of which have occurred — the vessel becomes an intricate, floating puzzle.

Johnson will have to unravel the complexity. He'll rely on ship diagrams and his own onboard measurements to re-create the vessel using an obscure maritime modeling software known as GHS — General HydroStatics. The model will allow him to simulate and test what will happen as water is transferred from tank to tank in an effort to use the weight of the liquid to roll the ship upright. If the model isn't accurate, the operation could end up sinking the ship.

Habib thinks Johnson is up to the task. In 2004 they worked together on a partially sunken passenger ferry near Sitka, Alaska. The hull was gashed open on a rock — water had flooded in everywhere. The US Coast Guard safety officer told Habib and Johnson to get off the ship, saying it was about to sink completely. It was too dangerous.

Habib refused. His point of view: It was his ship now, and he would do what he wanted. The safety officer reprimanded Habib and told him that no ship was worth "even the tip of your pinky."

Habib smiled. Insurance lawyers have calculated the value of a pinky — $14,000, tops — and that's far less than the value of a modern commercial vessel.

Johnson told the Coast Guard not to worry; the ferry would be floating again in three days at exactly 10:36 in the morning. The Coast Guard was skeptical but, three days later, as the tide peaked at 10:36 am, the ferry bobbed up and floated off the rock. It was a rush to be that right.

So when he gets the message inviting him to join the team headed to the Cougar Ace, his only question is: