Nigeria  Louisiana

Louisiana

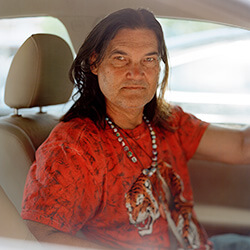

Igwe Udeh

I remember the first time I saw a cowboy. It was a surprise — because I didn't think cowboys existed anymore. I'd only seen them in movies. It was the fall of 1980 in Norman, Oklahoma. I was sitting in a classroom at the University of Oklahoma, where I was getting my master's degree in economics. A slim, tall man strolled in. His heels clicked as he walked. He wore a red-checkered shirt, thick denim jeans, brown leather boots, and a wide-brimmed hat that obscured his face. He took off his hat and set it down. The hat took up its own seat, and nobody dared to sit there. I stared at him, in awe of his confidence. In Nigeria there were nomads who raised cattle and wandered from place to place, but they had no style. This man was the first American cowboy I'd seen in real life, and I was amazed.

I'm from a small town in Nigeria called Abiriba. I'm a member of the Igbo tribe. Growing up, I watched all the American Westerns — the John Wayne movies, Clint Eastwood movies. I know all the lines from A Fistful of Dollars and The Good, the Bad and the Ugly — both of which I must have watched 50 times. There were peddlers who'd come to our village, show American movies on a projector, and sell us American products. So I'd always had a vision of the cowboy in the back of my head. Cowboys were a myth, a symbol to us, but when I came to America my professors were cowboys, my classmates were cowboys. Oklahoma was full of them.

When I left Nigeria, the country had just emerged from a very brutal civil war. The country was devastated, so if you could afford it, you left for better opportunities. I'd come to America to get my master's in economics at the University of Oklahoma. I was the only black man in my program, and one of the few in town. I quickly learned that there was no barbershop in Norman that could cut black hair. I let my Afro grow. My accent was thick; to Okies, unintelligible. Sometimes they'd pretend like they couldn't understand what I was saying. Some were rude, and I thought their attitude was … unpolished — let me put it that way. I'd go to churches where I was the only black person, and sometimes I'd be wearing traditional Nigerian garb like a dashiki or isiagu and no one would talk to me. They'd look at me like, "Why are you dressed like that?" I'd sit down and people would get up one by one from the pews and move somewhere else. I'd leave feeling rejected and alienated. I didn't become an American on the spot. I wanted people to know that I'm still African. They were proud of their culture, and I was proud of mine, too.

But I could also see the Igbo spirit in cowboy culture. The Igbo spirit is tenacious, and we are deeply connected to our land, which is rich and full of oil. I could see how much cowboys loved their land — they'd stay here forever, they would never leave it. Cowboys are unapologetic, too. Blunt. They do not care what other people think. I could imagine them a hundred years ago, when Oklahoma was still known for its quarries. They had to tough it out themselves. They could not depend on the government, they could not depend on anyone else. Coming from Nigeria, where the government was never on my side, I could identify with that.

It was easy to dress like a cowboy because that's what all the thrift stores sold — so eventually, I began to dress like one. I bought flannels and checkered shirts with silver glass buttons, second-hand jeans, brown leather boots that went up to my calf and made me taller. I couldn't afford the custom-stitched ones that other cowboys had. I tied a red bandanna around my neck because it reminded me of the white neckerchief my dad wore back in Nigeria. I even bought a Kawasaki motorcycle — the biggest one I could afford, even though I already had a car. It was my iron horse, and I rode it without a helmet because my Afro was too big. Everything about being a cowboy appealed to me, except chewing tobacco. I tried, but it always felt too disgusting. Back then, the floor of the university bathroom was covered in tobacco spit, and it made me cringe.

At first, people were confused about my new clothes. They'd never seen a foreigner with so thick an accent dressed up this way. They were tickled. The first time I walked into a classroom in my new cowboy getup, someone said, "Look at that! Igwe wants to be a cowboy." I smiled and replied, "Yes, I do."

I used to think about returning home and buying land in Nigeria — I thought that was where my kids were going to grow up. But that has changed. If I'm ever rich enough, I'd like to own a cattle ranch here. Maybe I'll go west, where there are a lot of trees and no swamp. I was invited to a classmate's cattle ranch once, and I was in awe. We played horseshoes and went skeet shooting. At the end of the day we ate very nice steak together. There was a lot of it. You could eat meat until it dropped out of your nose.