Mexico  California

California

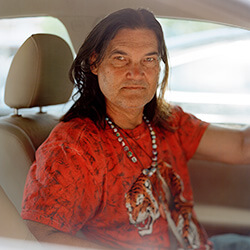

Reyna Pacheco

The first time I played, I was 13 and undocumented. There were 30 of us packed onto a court. My school rented squash courts at a private club in Mira Mesa, San Diego, and divided them up with a big makeshift wall. On one side tutors helped with homework; against the other, we hit balls and watched them bounce high and hang in the air. I'd felt like I was barely surviving school that year — I'd been fighting other kids and had my mind set on leaving. I couldn't understand the point of college. My brother had dropped out of high school, my mom spent hours cleaning others' homes. But here was one thing I could focus on, swing at.

I wasn't great that first time. To be honest, I was the last kid to hold a racquet properly. But something about it appealed to me. I started bringing a racquet home — using it to pick up t-shirts and oranges. It became like an extension of my hand and made me feel kind of powerful. My brother kept asking me why I practiced this thing from the rich part of town and all I could say was, "It's different."

And it's true. Squash isn't accessible like soccer. There's no pick-up in neighborhood parks. It's played in a white cube. I could only go to the courts when paying members weren't using them. A lot of kids in America play squash to get into college. Their parents belong to private clubs, invest in lessons, and dream of the Ivy League. My mom didn't even feel comfortable watching me play. She'd say, "Reyna, look, my shirt isn't even clean enough for me to walk in there."

The courts I had to use were 18 miles from my home; a thirty-minute drive if you have a car. My mom and stepdad needed their car for work, or sometimes didn't have enough money for gasoline. So I would take a three-hour bus ride at 4 a.m., hit balls from seven to eight, take another bus to school, go back to the courts at around 5 p.m., and then head home. Sometimes if I ran late I'd have to race the bus from one stop to the next, or pound on doors until they opened, or even sprint into the middle of the street and demand the driver let me in.

I was surprised at how quickly I improved. I learned to volley on the side walls and came away from matches with scraped knees from battle. I couldn't take private lessons, but my coach, Renato Paiva, was a former Brazilian squash champion whose practices were academic quizzes and endless runs. With him I was always thinking, I must do more, more and more. This is why he made me team captain, even after I lost my very, very first match. That day I dove, I fell, and Renato said, "You have fighting spirit." And so I started planning my comeback.

Outside of practice, this game was a foreign world. Most tournaments are at East Coast boarding schools. I'd take five-hour plane rides with my racquet and sleep on the hotel room couches of my competitors. They'd be in their own made-up beds, and if they were nice enough to let me, I would sleep on the floor near the coffee table. And when we went to warm up, they'd be dressed in beautiful polyester shirts with red and white stripes. These are the jerseys you get when representing the U.S. in squash internationally. People I played with had tons of them — they'd hang out of bags and sit neatly in lockers. But I couldn't wear them, even when I was winning enough titles to become Top 15. I was still undocumented. And that meant that I couldn't play in sanctioned events. I couldn't even travel the world. I could tell that these parents buying $300 hotel rooms and kids with laundered jerseys weren't able to understand what brought me to the court, why I stayed.

It wasn't because this sport was different. It didn't feel that way to me anymore. During tournaments, I'd hit the ball, and it'd always come back. This return always had something unexpected — spin, bounce, the direction of my opponent's feet. I had to be aware, constantly pushing and perfecting and ready for my next shot. This immediacy fit how I was living — at school where I didn't know if I'd be in the country for our next exam, and at home where we turned boxes into chairs and wondered when the next check would come in. I had to take it all day by day. Squash had a rhythm that matched my life.

There was a game that my friend's father, Dickon Pownall-Gray, played with his wife: They would sit at bars, look at people, and guess: "That woman in velvet is a fashion editor," "The person reading O Globo is a translator." One day, they saw a guy sitting surrounded by books, looking studious. "An academic." "A Wall Street man." They had to ask. He turned out to be an immigration lawyer at one of New York City's biggest law firms. Mr. Pownall-Gray wanted me to have the same opportunities as his own daughter; he told this lawyer about my case. I don't know what he said. What I know is that the lawyer took me on pro bono and I agreed to trust him, though I was nervous. My family had tried to apply once before and a lawyer told us, "Don't try again, you're going to get kicked out of this country." But with this lawyer, I filled out a lengthy application, got fingerprinted, and went in for my interview. Just as all my classmates were beginning to apply to college, I got an envelope. A totally standard one; USPS Priority. My green card had arrived, but it still felt like an impossibility.

Now, I'm able to travel the world. I'm asked questions about the election, about walls, about growing up in a place that had crime and drugs. And it's odd because I'm the American — but I'm also Mexican. Residency doesn't mean I'm not thinking about my identity. It doesn't make me feel like I definitely belong. I'm always adjusting to new places and people, and that's part of life and training and squash. Things are never guaranteed. All I know is that on the court I feel safe to push boundaries, to set goals. On July 8, 2016, I played in my first U.S. Federation event. I wore a shirt with a red, white, and blue logo. Before putting it on, I held it in my hands and cried.